HackTheBox: Postman - Writeup

Overview

Postman was one of the easy Linux boxes available on HTB. As I’ve never really done any other box before, I was eager to give this one a try and dived right in.

Opening up Postman in Firefox revealed the webpage:

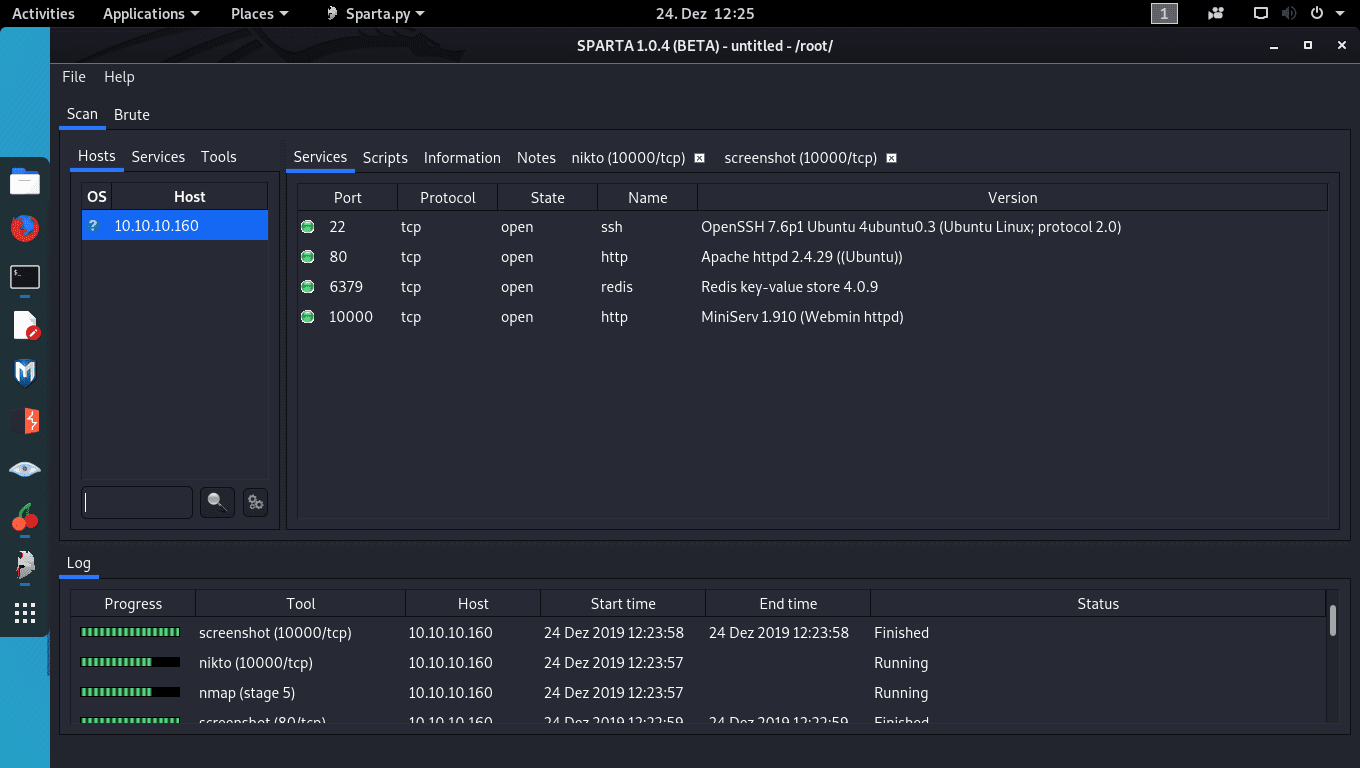

Closing the dialogue revealed a clickable mouse icon, but that led to a non-existant section tag. There’s no inputs or login fields anywhere; let’s see what Sparta has to say about this box. The port scan definitely revealed something interesting:

There’s both Redis v4.0.9 and Webmin 1.910 installed on this system, and both seem to be easily accessible. Nikto revealed nothing interesting on either port 80 or 10000 (where Webmin runs). At this point, I didn’t see any value in port 80 and decided to focus on Redis instead. Connecting to it via Telnet worked:

As we can see, we don’t even have to authenticate to execute any command on this Redis server. I started playing around a bit with EVAL and the likes, but got nowhere. After a bit of searching, I found this blog post, which details a Remote Command Execution vulnerability in Redis v4.0.9 or lower.

The short explanation: With a few commands, we can abuse Redis to push our own SSH key into the Redis users’ authorized_keys file, allowing us to log in via ssh later.

The blog post has a full write up on how this is achieved. Let’s see the exploit in practice:

We now own the Redis user. Our “home” directory is /var/lib/redis/. The user flag is in /home/Matt/user.txt, which is not readable by Redis user. The next question is: How do we get to Matt?

Owning user

Enumeration is key. I deployed this script to see if there’s anything immediately obvious we can use to gain access. There were quite a few configuration files (SSH, Apache, etc.) readable as Redis user, but nothing that was editable. There were no running cronjobs that could be abused, and the script found no SSH keys. Checking services running as root with ps -aux | grep root, I found that Webmin and a few other services were running as root. This is important for later, but cannot be used to gain access to Matt.

At this point I looped back around to Webmin, especially since I had access to all the files found in /usr/share/webmin/. I played around with it for a few hours, trying to see if I could maybe use change_password.pl or similar to my advantage. However, I found the actual solution purely by chance running through some files: /opt/id_rsa.bak.

That was a backup of a private key, presumably used by user Matt. I extracted the key from the server, put it into my .ssh folder and immediately tried to connect to the server again:

The key was protected by an unknown passphrase, which was to be expected. However, with John The Ripper it’s an easy fix. We simply convert the private key to a John-readable Hash, take an appropriate wordlist and try our luck:

Unfortunately, we aren’t allowed to connect as Matt via SSH. Turns out that there is a Denyusers Matt directive in the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file, which prohibits Matt from logging in via SSH. I logged back in as the Redis user and instead used su Matt with the previously obtained password, which worked. We successfully owned Matt.

Owning root

Having submitted the user flag found in /home/Matt/user.txt, it was time to go on to root. This is the time for Webmin to shine (or break things, however you look at it).

Webmin is basically a web-based admin interface for everything Unix. Everything that’s possible as a root user via terminal is possible in Webmin via GUI. Regular users can also log into Webmin and do things, depending on their permissions. Searching for known vulnerabilities for Webmin 1.910, only one relevant vulnerability comes up.

This vulnerability requires the user to have access to the “Package Updates” functionality. I quickly logged into Webmin as Matt (credentials are the same as on the Unix system) to verify that he has access to Package Updates. Afterwards, I fired up Metasploit Framework and started preparing the exploit. The only necessary info for the exploit is the Target Server IP, username, Password and the IP of my system (used for the reverse shell). Everything else is done by MSF.

Let’s see what that looks like in action:

Conclusion

Owning user was definitely harder than owning root on this box. The jump from Matt to root was, thanks to Metasploit Framework, exceptionally easy. Nevertheless, it was definitely a fun box.

Reply by email Back to top