HackTheBox: Baby Challenge - Writeup

Published: 2021-05-20I’ve been waiting to check out Ghidra and some Reverse Engineering for a while now, and I figured that an easy HTB Challenge would be a good way to start, especially since this one’s called Baby.

Initial setup

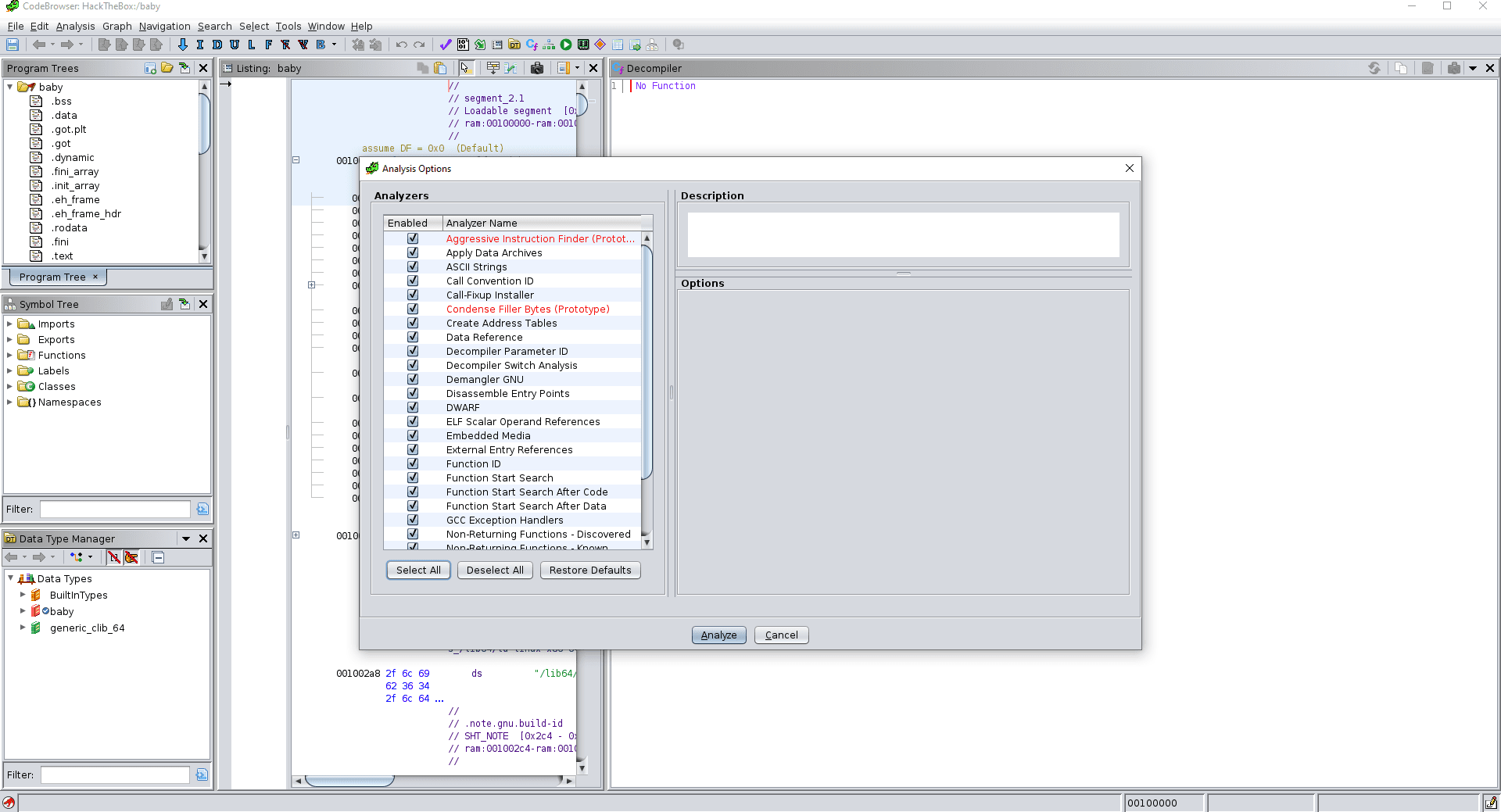

After setting up Ghidra and downloading the Baby file, it’s simply a matter of importing it into Ghidra. When prompted to analyze it, make sure to Select All and then let it analyze; this step should not take more than a minute or two.

Understanding Ghidra

If you’ve never used Ghidra before (like me!), it’s going to be a bit overwhelming at first to understand everything. Lucky for us, the Baby file is extremely small, making analysis way easier.

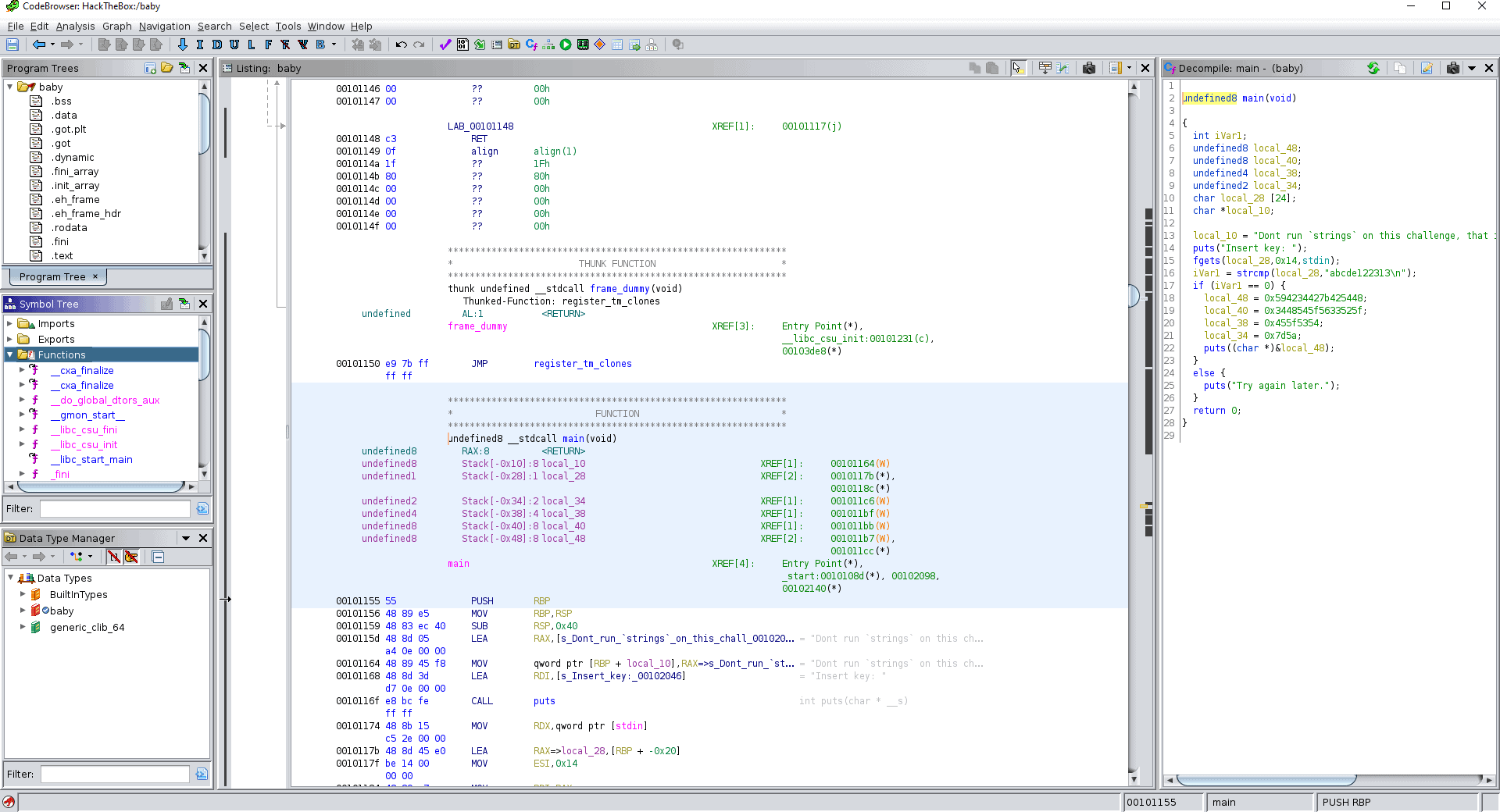

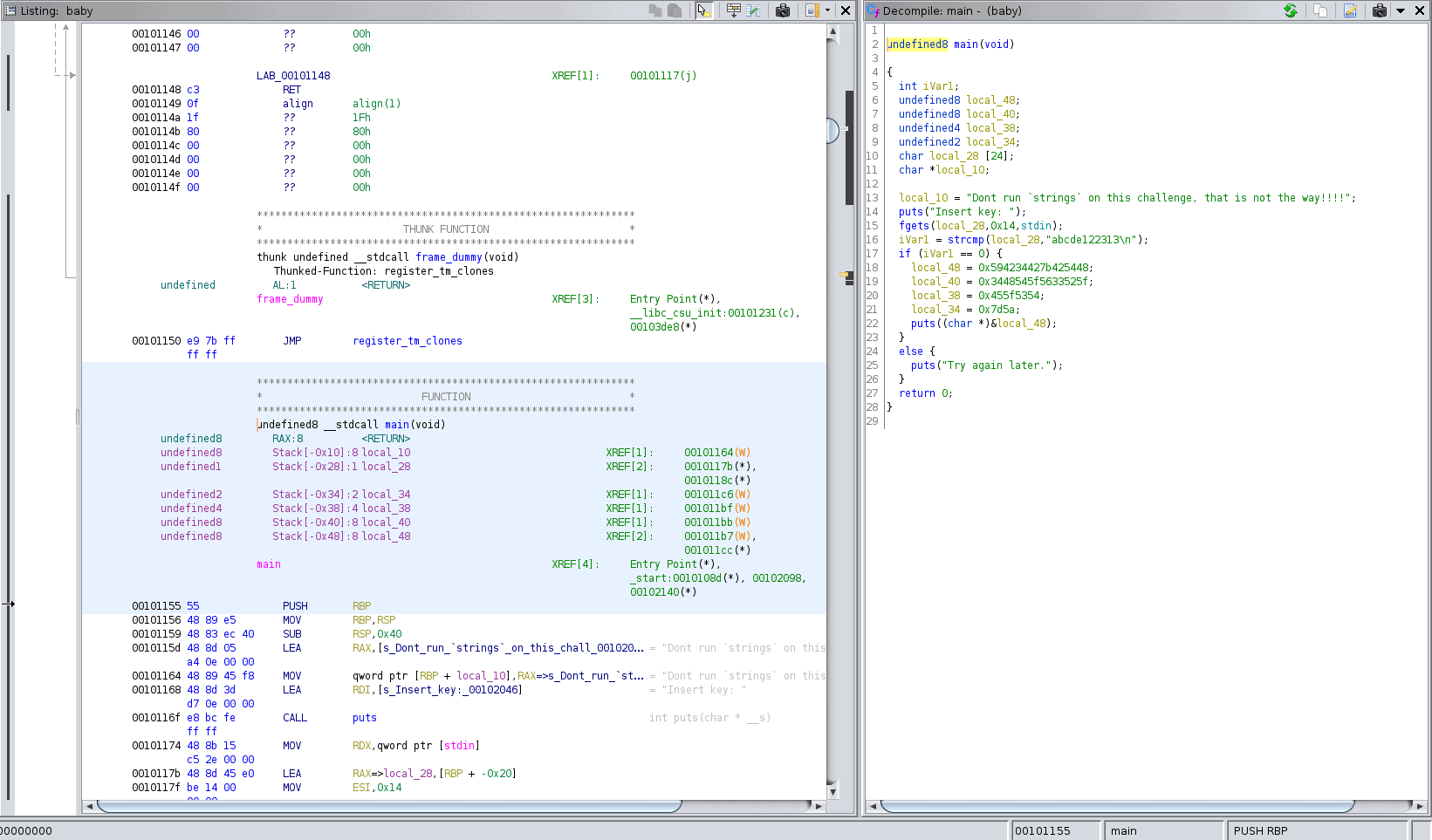

The standard configuration should show the Program Tree, the Symbol Tree, Data Type Manager, Listing and the Decompile window:

Let’s go over the interesting sections for this challenge.

Symbol Tree

The symbol tree shows us all the interesting bits and pieces like Functions, Labels and Classes. It’s very useful for quickly navigating programs and finding useful functions like main(), the entry point to C functions.

Listing

The Listing shows us the entire program, with the Assembly instructions and all the function calls printed out. Moving about, we can double click on any function and see the details in the Decompile window.

Decompile

Here, any function selected in the Listing will be shown in detail. This is where we’ll spend most of our time today as we finish this challenge.

Solving the challenge

Looking through the functions present in the Symbol Tree, we can quickly deduce that this is, in fact, a C program, because we’ve got external functions like fgets, put and strcmp. This means that there is also a main() function, our entry point. Let’s open that up and see what we are working with:

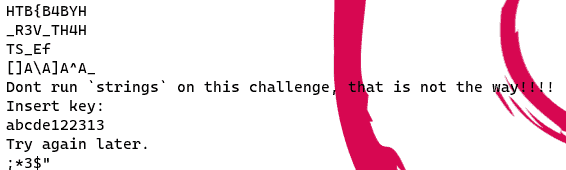

We’ll get to the whole “Don’t run ‘strings’ on this challenge” in a second.

To solve this, you don’t even need basic C skills; just googling your way through is enough. In this case, the program starts out with a puts(string) call, which simply outputs the string “Insert key: “. The actual prompt (input) is realized using fgets(variable to store input, length of input, stream). This stores the user input in the variable local_28. As you’ll no doubt have already noticed, our input is then compared to the hardcoded string abcde122313. The newline is not part of the comparison.

strcmp() returns 0 when both strings are equal, yielding our flag: HTB{####}.

There are of course multiple ways to do this, so let’s try those out too.

Running strings on the challenge

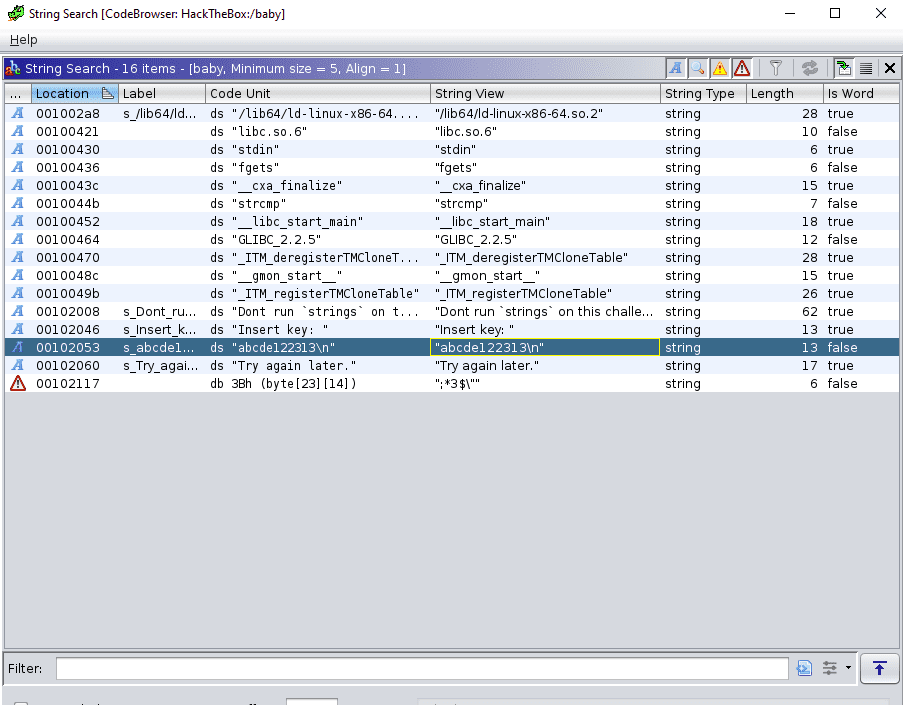

This time, we’ll do exactly the opposite of what the program is telling us: Run strings. This is a program that comes pre-installed with Debian (and, I think, any Linux distro out there). What it does is output all of the used strings inside the program in the order they appear. You can either run this from the terminal or inside Ghidra using Search > For Strings. The output is almost the same:

Using strings allows us to sort of see most of the flag already. However, we are immediately able to see the string that our input is being compared to. Even if you hadn’t taken a look at the program inside Ghidra before, simply by seeing the location of the string (right after “Insert key: ”) should be a sign that this might be the string used for comparison.

Picking out the comparison string and running the program will again yield the flag.

Scripting

If we go back to our main() function, we can see that if the string comparison is successful, it casts the variable local_48 to a char and then outputs it using puts(). The string is stored using hexadecimal, presumably as a form of very simple obfuscation. Using an ASCII table, we can quickly see which two numbers represent one ASCII character in the variable local_48:

| Hex | Character |

|---|---|

| 59 | Y |

| 42 | B |

| 34 | 4 |

| 42 | B |

| 7b | (left curly bracket) |

| 42 | B |

| 54 | T |

| 48 | H |

But wait! That’s in reverse; we know our flags start with HTB. There’s an additional step in the obfuscation there. Using this knowledge, we can fire up a quick Python oneliner to convert hex to ASCII and then reverse the string:

import sys

print(bytearray.fromhex(sys.argv[1]).decode()[::-1])An important thing to note here: In this example, there’s 4 variables in play to display the flag. In reality, the flag was probably put into one variable, but still stored in hexadecimal form. Ghidra split this hex value into 4 variables; no idea why, but it’s a thing. When working with this hex value, simply start from the bottom variable (in this case, local_34) and end at the top variable (local_48). Combined, the call to the Python script looks like this:

python3 char-checker.py 7d5a455f53543448545f5633525f594234427b425448

HTB{####}Conclusion

This was a fun little challenge to get into Ghidra and Reversing in general, but I’m obviously no expert in any of this. Still, there’s plenty of hard challenges to come that I look forward to solving.